You’ll already know that I’m one for data and detailed information. It doesn’t matter if this is in the field of running, computing, music and probably even baking. If there’s a chance of a slice of data to pour over, I’ll probably not be far away.

A bit of background

One area of data collection that I followed from the periphery was optical heart rate (OHR) measurement. OHR has been around for a number of years now, however it’s only been in the last maybe 3 years that the sensors fitted to many of the major sports watches have matured enough to be able to compete with the more traditional chest-strap mounted modules.

This gradual improvement in the technology is nothing to be surprised about; indeed it took a good while before the chest straps were considered to be accurate enough to be used as part of a training regimen, rather than a nice-to-have number on the bottom edge of the page.

With the questionable data being a problem, the major sports watch manufacturers were clearly hesitant about incorporating the OHR units in their watches; the last thing they would be wanting is the ‘new’ option being terrible and turning people away from their devices.

From the point of view of Garmin, their ‘breakthrough’ running watch with OHR appeared to be the Forerunner 235. There was already a higher-end watch with such a sensor, but the 235 marked a point where the inclusion of OHR was a ‘standard’ rather than an optional extra. This watch, some 3 years old now, is amazingly still classed within their ‘current’ line-up which is astounding really in a world of annual updates to models.

A non-early adopter

At the time, I went for its bigger brother option, the FR 630 as I wanted (surprise surprise) more data metrics more than having the built in OHR unit.

As it happens, the 630 remained a current watch for a fraction of the time of the 235 and I had very mixed results. The first watch developed all sorts of amnesia and was eventually replaced under warranty by Garmin. The second watch behaved a lot better, although I was very sceptical about some of the data it produced.

I waited until spring 2018 when it’s ‘replacement’ (bearing in mind it had long since been a ‘current’ model) was released. The Forerunner 645 came with all of the data stuff, plus built in OHR as well as an option to be able to store music on it. This latter option was apparently something that lots of people wanted, but something that I had no interest in. So I purchased the basic 645.

It’s worth noting that much of the clever data (called ‘Running Dynamics’ in Garmin-speak) on the 645 actually required either a chest-strap or a separate module aside from the watch to be able to record.

Upon getting my shiny new watch, I actually managed to misplace my old chest-strap for about 6 months. Not intentionally, but it ended up left in a coat pocket and I didn’t realise until the warmth of the summer went and I reached for my fleece and rediscovered it!

The net result was that for the limited training I undertook during the summer months of 2018, all my HR data was provided by the optical sensor on the watch. I took a vague interest in it only as I wasn’t engaged in a training plan for much of this time. But it didn’t look unreasonable when I did have a glance.

Returning to training

I began to up my training in earnest during the back-end of September, really when I discovered just how much fitness I’d lost over the summer! It was back to interval sessions on the track and focusing my running both on and off-road. Following a Facebook discussion between running coaches about utilising Maximum Aerobic Function (MAF) in training, I started to focus on the data that the OHR was actually producing.

Turns out it wasn’t quite what I was expecting.

My run yesterday was in line with the MAF training. In short, it’s a run who’s pace and effort is directed by a HR figure based upon the athlete’s age. This is actually a very simplified calculation at 180 BPM – AGE but it’s clearly been worked out to be a reasonable average over a lot of people. The result is a relatively low HR to run to, with the theory being that over time, if one runs to this HR, their aerobic fitness will improve and thus they will be able to run at a faster rate at that HR.

So to do the run is quite simple. Get warmed up and then run, keeping that MAF figure as the maximum your HR should go to; if it goes up, you need to slow down. Simple!

Except it does rely on one big thing. That the HR data is actually right. And this is where things started to go awry.

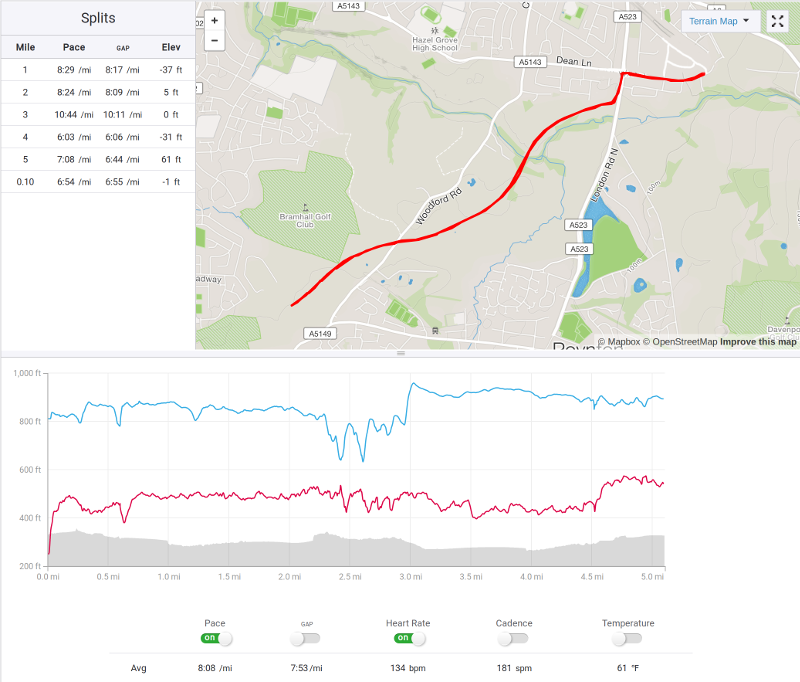

Here’s the trace:

My HR was sitting quite nicely at or around the MAF figure as I tootled up the new bypass. But then my HR began to rise. And rise further. It was still going up when I was walking (the blue trace shows my pace and you’ll see in the middle it drops right down. The HR data, in red, does not). Basically it made no sense at all. Now I am aware of limitations in wrist-based HR devices when it gets cold as the signal can become weaker, but whatever the watch was listening to, it certainly wasn’t my heart! In fact to prove the point, I decided to turn back and run a mile at my 5k pace, which was something like 3 min/mile faster than the previous miles. In theory, the HR should be much higher than before as my body was working harder. In practice, the recorded HR was about 20 BPM lower than when I was walking (see the section mile 3 – mile 4)! Thus demonstrating that the data was complete nonsense.

It did draw my concerns to how we work with data. In this case, the data was so obviously incorrect that I was quickly aware of the fact and abandoned using it. However, what if it hadn’t been that clear-cut. I would have been training to a figure that wasn’t actually based upon what my body was doing in practice. That’s bad enough to a relatively trained-eye, but what happens when someone without that level of experience happened upon a HR-related training method and followed it? Definitely a concern.

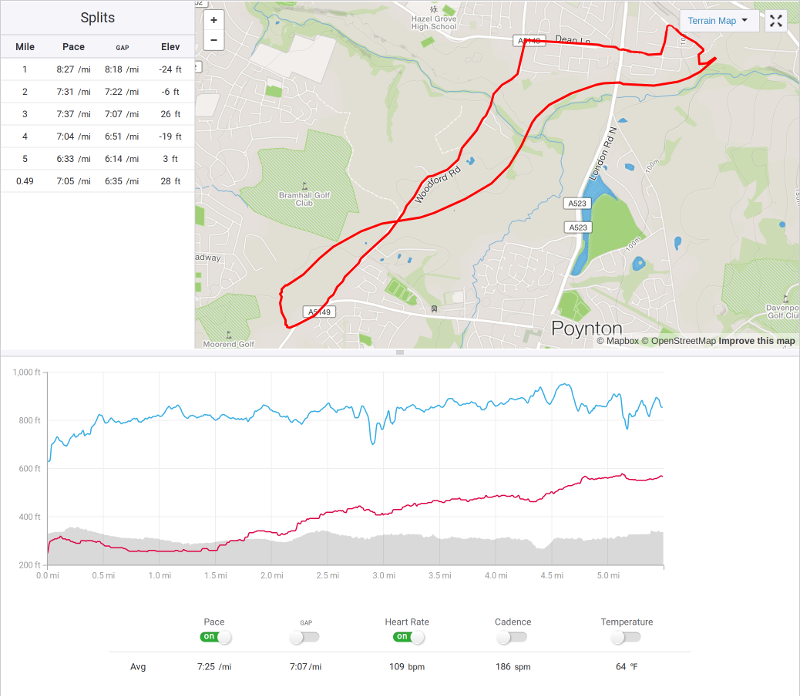

As it happens, when I went out today for a similar run I took the old and trusty HR strap. And guess what? The data was completely garbage again! HR seemed to sit about about 80BPM for the first 1.5 miles before gradually rising, even though I was somewhere between 10k and HM pace for the majority of the run!

I decided that then next step would be to do a hard reset of the watch to delete all data from it and to get all the settings back to factory mode. I’m hopeful that this clears the gremlins out, but I’ll post again with the new data once I have it and we’ll see if things have improved.

Learning Points

It all draws back to an adage I picked up during an A-Level physics lesson. Just because some numbers have been produced by a system, doesn’t mean they’re right. So my take home message is to accept the data generated but with a suspicious mind. Does it seem reasonable? Is it consistent with my feelings when out on the run itself? Your own perception of the effort during the run should give you an answer to both questions. Only then can we dig into that data to try to learn more. If it’s duff, then all information inside it is questionable.

Be the first to comment on "HR data woes"